By Reba Kocher

Listen to this blog post here: cecropia.mp3

Cecropia moth. Photograph by Cathy Keifer/Shutterstock.

Once again, happy National Moth Week! Did you know that you could find North America’s largest native moth (and in my opinion one of the most beautiful) in your backyard? They’re called Hyalophora cecropia. They belong to the family Saturniidae, also known as giant silk moths. They can be found all over the United States and into the southern Canadian provinces.

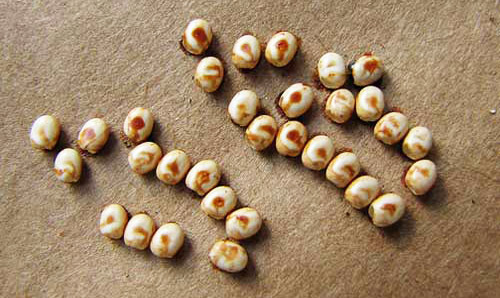

Their host plants are usually maples, but you can also find them on cherry and birch trees. Unlike a lot of Lepidoptera, they lay their eggs on both sides of the leaves. Cecropia eggs are white and reddish brown. After they hatch, their caterpillars will actually go through five instar stages, each one lasting a week to ten days. During the first stage, they are small and black. In the second stage, they get a little bigger and they are yellow with bristles. The third through fifth stages are green with bright yellow, blue, and red/orange bristles. As they move into stage five, their colors begin to dull. Unlike most other caterpillars with bristles, cecropia are not poisonous.

When they are ready to pupate, they will spin a large dark brown silk cocoon. The cocoon may look either baggy or compact, and it is believed that this is to combat various environmental conditions. Finally, the adults emerge, usually around 4:00A.M.-6:00A.M. in spring or early summer. It takes them a few hours to dry before they can open their wings and fly. As adults, they do not have functional mouths or digestive systems. Because of this, they only live for about two weeks. During this time, their main objective is to mate. Females will emit a pheromone, and using his antenna, the males smell it and will travel up to 7 miles to mate. Once they pair up, they will begin to mate in the early morning into the evening. You can see the whole life cycle here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D8YU0UoLLuE

Eggs. Photograph by David Britton.

1st Instar. Photograph by David Britton.

2nd Instar. Photograph by David Britton.

3rd Instar. Photograph by David Britton.

4th Instar. Photograph by David Britton.

5th Instar. Photograph by David Britton.

Adult. Photograph by David Britton.

Adults mating in Licking County. Photograph by Jennifer Bush.

As wonderful as these moths are, unfortunately, their numbers are declining. Several factors contributed to this including: squirrels eating them, a destruction of woodlands, people leaving their outdoor lights on, parasitoids, and the presence of ladybugs. The reason that outdoor lights pose a problem for moths of all species is that scientists believe that artificial lights interfere with the moths’ navigation systems. They use the moon for direction and use this to find a direct path to wherever they’re going. That’s why when you see a moth outside your porch light they are flying around in a circle. They can’t figure out a direct flight path. As mentioned, parasitoids are also a huge problem for these moths. Parasitoids include parasitic wasps and parasitic flies. The parasitoid will lay eggs inside or on top of a young caterpillar, then once the eggs hatch, the larvae will eat the organs and muscles of the caterpillar. They also force caterpillars to pupate sooner than they usually would. This allows the parasitoid to feast upon the resting pupa and this, obviously, leads to the death of the pupa. Unfortunately, there has been an increase of caterpillars deaths this way because a parasitic fly was introduced in the United States to eat the European Gypsy Moth, and while it does eat the gypsy moth, it also eats cecropia. Similarly, the ladybugs, who are generally released to eat aphids, will occasionally mistake cecropia eggs for aphids.

Though it is too late to see any cecropia this year, be on the lookout next year! And please try to turn off your porch lights at night. Think about the moths!

Watch this awesome video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=27&v=MKd9U_Y4mas

References & Further Reading:

http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/bfly/moth2/cecropia_moth.htm

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0174023

https://extension.umaine.edu/home-and-garden-ipm/fact-sheets/common-name-listing/cecropia-moth/

https://extension2.missouri.edu/ipm1019#Cecropia